The Cervix Has Nerves

The Cervix Has Nerves

As many of us know through personal experience, a common justification of misogynist violence inflicted on us is that our bodies can’t feel pain and therefore we aren’t deserving of procedures that minimize pain, or medications to reduce pain. This is part of a long history of medical harm, which got its foundation by performing excruciating experiments on enslaved Africans, especially African women.

Because I’m reading Medical Apartheid right now, and I encourage you to do so as well, I decided it was a good time to talk about a really important topic that continues to go unheard: cervical innervation.

Anatomy

The cervix is a 2-3cm long passageway located at the lower part of the uterus and which opens into the vaginal canal. It’s not just “the neck of the uterus” as the etymology denotes. Beyond being a passageway, the cervix has complex glands which secrete different kinds of cervical mucus, protecting the body from infection by creating a mucus plug, and nourishing and transporting sperm upwards during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. The cervix has nerves which transport important information to the brain throughout a persons life.

I’m grateful for the many cervix activists who are pushing for more awareness about the fact that the cervix has nerves, that the cervix is sexual, and that the cervix can tell you about your current fertility status. Most of us only hear about the cervix in relation to cervical cancer, HPV, IUDs, pregnancy, or a pap smear.

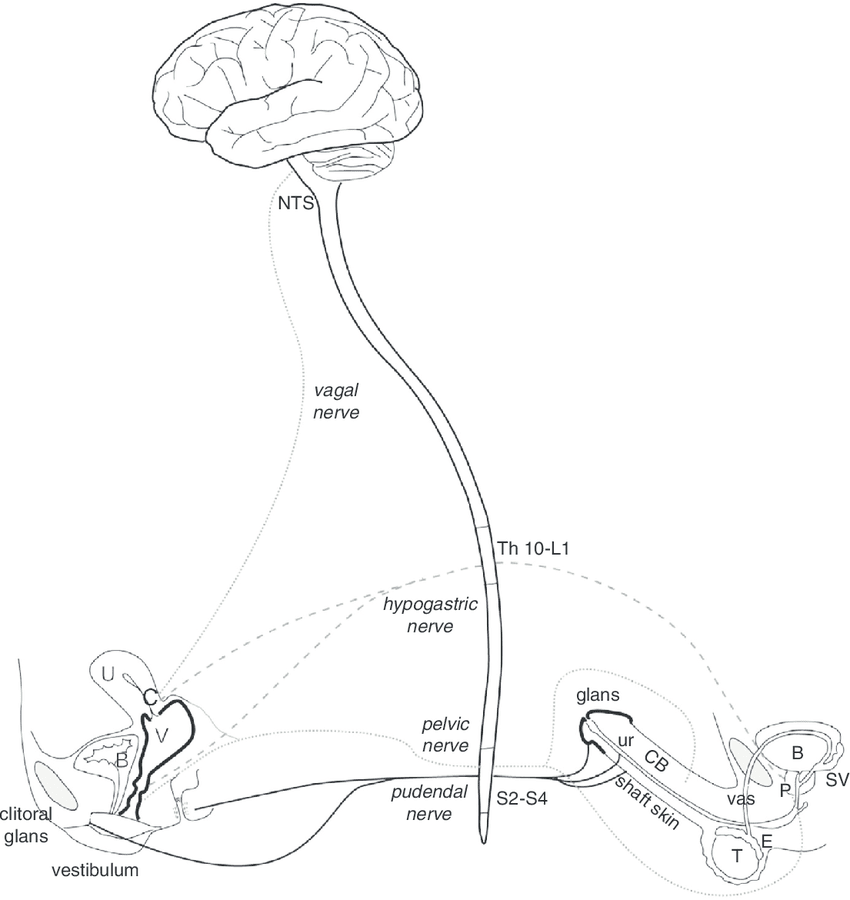

If you start to look into cervical neurology, you will have a hard time finding much research on it. There are only a few people studying it, even in the year 2020. We now know that the cervix does have nerves, 3 pairs of nerves in fact, that travel to the left and right sides of the brain. These include the pelvic nerve, hypogastric nerve, and the vagus nerve, which bypasses the spinal cord and sends information directly from the cervix to the brain. This is particularly remarkable because, as Barry Komisaruk, PhD, from Rutgers University explained, the “cervix receives sensory input from three different pairs of nerves,” — pelvic, hypogastric, and vagus — “and I don’t know of any other organ that does [that].” It’s very rare to have an organ with triple innervation, and the cervix has just that. There is also a fourth nerve involved in human female anatomy, the pudendal nerve which connects the clitoris to the brain.

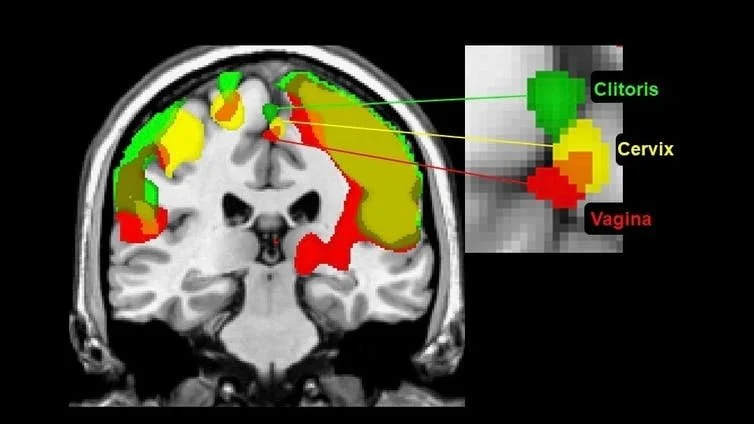

I love this graphic because it shows the innervation of the reproductive organs and how they connect to the brain.

Now let’s talk about gynecology.

Gynecologists don’t typically study cervical neurology in medical school. Even worse, doctors are well known for gaslighting people who experience side effects from cervical procedures, often passing them off as psychological, when there is legitimate nerve damage and scar tissue. All of these attitudes are informed by the incorrect assumption that the “cervix has no nerves.”

So where did this idea that the cervix “has no nerves” come from?

It goes back to the famous Kinsey Reports, which were two books written about human sexuality and taboo subjects related to sex in 1953. Kinsey researchers ran an experiment where they “gently stroked” the cervix with a “glass, metal, or cotton tipped probe,” where only 5% of the participants reported they could feel it. This is the basis for the conclusion in the report. In “Sexual Response in the Human Female” Kinsey states “All of the clinical and experimental data shows that the surface of the cervix is the most completely insensitive part of the female genital anatomy.” This statement has been used to conclude that the cervix has no nerves. It has further served as a fraudulent justification for the dismissal of the many testimonials of people with cervixes, that we can indeed feel our cervixes.

The history gets even more complicated. This erroneous assumption may be the result of Kinsey himself cherry picking information out of the research, as the Kinsey researchers also stimulated the cervix of the same group of women in the study with “distinct pressure” using “an object larger than a probe,” and when they did, 84% of the participants reported they could feel it!

Too often we find that common myths in gynecology or in relation to the human female body in general are based in flawed or faulty research, but because they are parroted by supposed “authorities” they continue to be perpetuated in modern scientific thinking. Of course, this is to the detriment of anyone who has a cervical procedure of some kind in their lifetime, to which there are millions of people affected by these harmful falsehoods.

What do we know about cervical innervation?

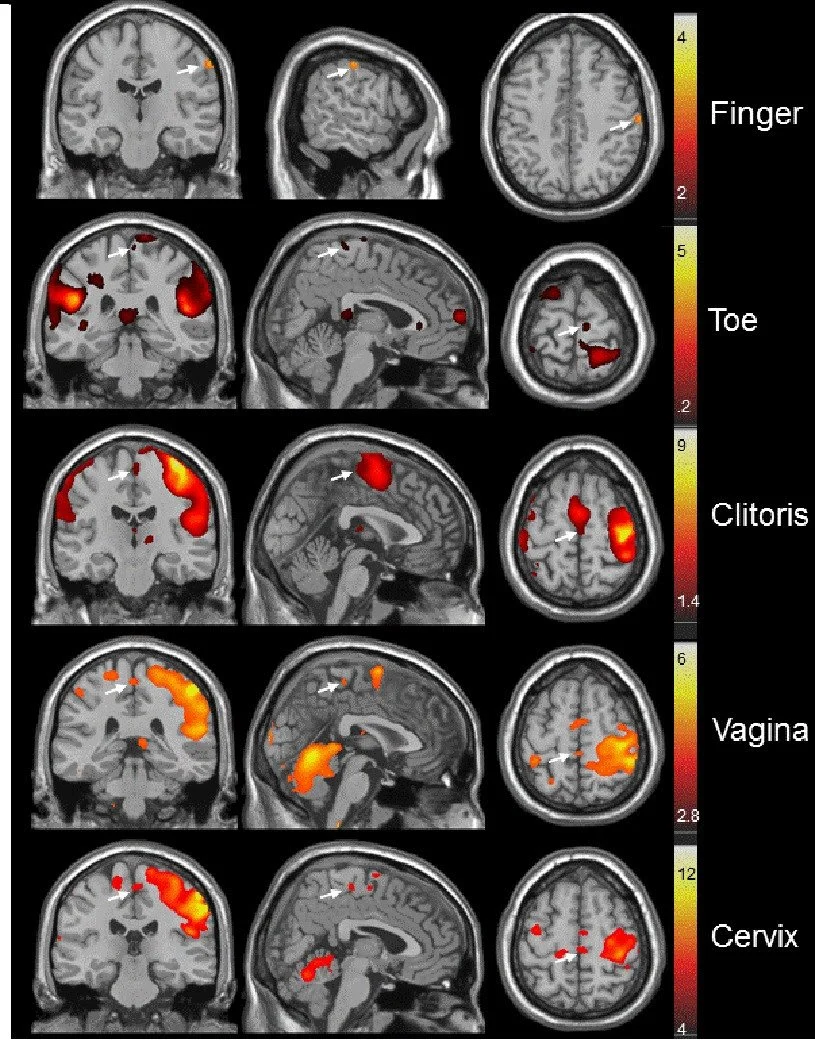

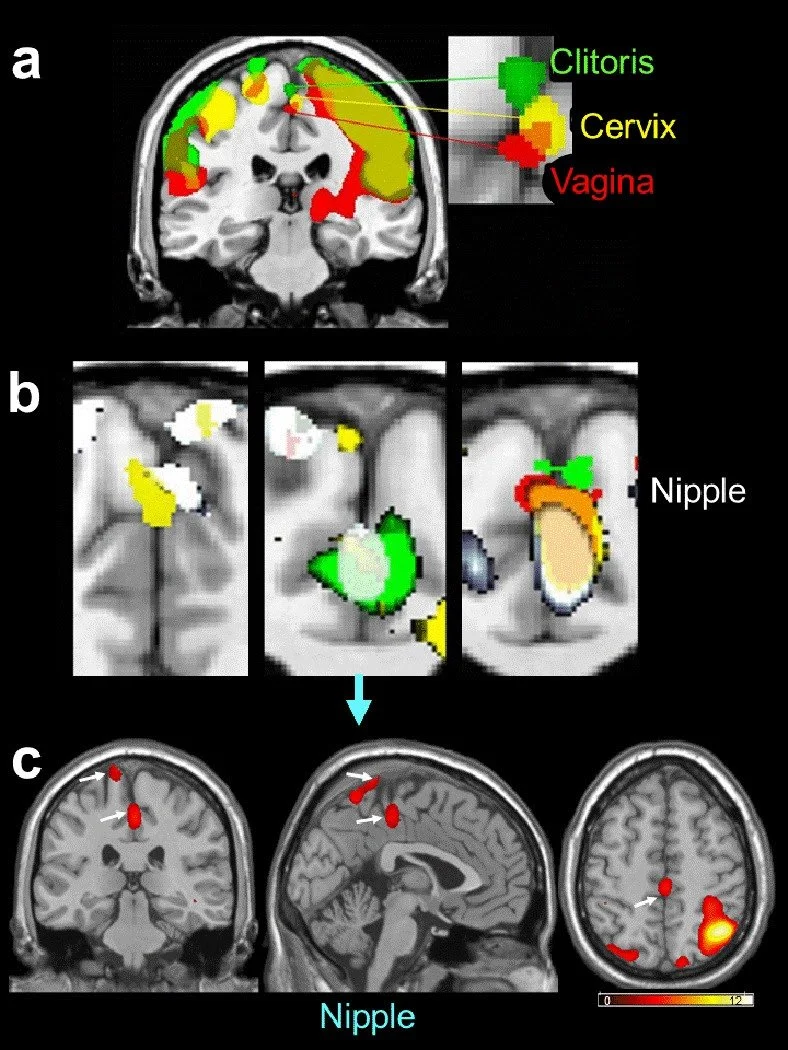

Thanks to the work of Barry Komisaruk, PhD, we now have a representation of the genitals in the sensory cortex in people with uteruses. Until his research was published in 2012, we could only rely on the original map of the representation of the genitals in the sensory cortex “in humans” -- which was only tested in cis men. [1] You’ll find that research that was tested only in cis men is commonly used to represent all human beings, a travesty in many ways. The study used functional MRI technology to measure stimulation from different parts of the body, like the cervix, vagina, clitoris, and nipples.

[1]

Here’s what they found.

The clitoris, cervix, and vagina send nerve impulses to the same area in the remedial paracentral lobule of the brain, at the top of the head between the two halves of the brain

Stimulating the nipples also lights up the same part of the brain, surprising researchers because of its physical distance from the genitals

The sensory cortical regions activated by each of the three genital regions are “to some extent separable and distinct”

These findings are evidence that vaginal and cervical stimulation is NOT just an indirect stimulation of the clitoris, but that these areas have distinct sensory projections

These findings support anecdotal evidence that we have which suggests that there are other types of orgasms beyond solely the clitoral orgasm.

These conclusions are groundbreaking! They fly in the face of much of what we are told by practitioners today. Although the research is going on 8 years old, not many gynecologists have reformed their attitudes about the cervix being in any way capable of sexual pleasure.

Another study looked at women with complete spinal cord injury who have noted vaginal-cervical perceptual awareness. Because the vagus nerve connects the cervix to the brain while bypassing the spinal cord, they studied the pathway from the cervix to the brain visualized with functional MRI technology. They found that in all four women with “complete” injury, and one with significant but “incomplete” spinal cord injury, all showed activation of the nucleus tractus solitarii region of the medulla oblongata, to which the vagus nerves project, when activated with vaginal-cervical self stimulation. Three of the women experienced orgasm, as shown by “activation of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, medial amygdala, anterior cingulate, frontal, parietal, and insular cortices, and cerebellum.” The researchers concluded that “Vagus nerves provide a spinal cord-bypass pathway for vaginal-cervical sensibility in women with complete spinal cord injury above the level of entry into spinal cord of the known genitospinal nerves.” [2]

The Cervix And Medical Harm

One of the most obvious anecdotal pushbacks on the statement “the cervix has no nerves” is from those of us who have had a pap smear. A pap smear is an optional cervical screening that detects early cellular changes which may either clear up on their own, or potentially (but rarely) develop into cervical cancer. To perform the test, a speculum is used to be able to see the cervix, and then a cervical spatula or brush is inserted and scraped over the ectocervix which protrudes into the vagina. The cells collected are then examined. Many people with cervixes report pain or discomfort with this procedure.

But it doesn’t end there. What happens if your test results come back as abnormal? Usually you will be steered to a cone biopsy procedure or LEEP/LLETZ procedure to remove the abnormal cells. This seems all well and good until you read the testimonials of those who have suffered the effects of these procedures. Many report physical, sexual, and psychological pain. Although most are told the procedure removes “just a few abnormal cells” the truth is that the procedure involves removing about 2cm of cervical cells through excising (cutting) and then cauterizing (burning) the ectocervix.

Dr Irwin Goldstein, MD, is the director of San Diego Sexual Medicine explains that the “cervix brain connection is severed [during a LEEP], and that results in the inability to transfer critical sensory afferent information from the cervix to the critical brain areas.”

In regards to the multiple reports of sexual dysfunction and loss of orgasm, as well as general depression, Golstein says “The cervix is a sexual organ among other things, and during the LEEP, you chop out a good part of it where all of the nerves are.”

Cervical activists have even made the comparison that these procedures are a form of female genital mutilation. Rarely, if ever, is the procedure explained in proper detail to patients, and it’s even rarer for the practitioner to obtain fully informed consent from the patient before performing the procedure.

If you want to read more testimonials from LEEP/LLETZ patients: - Asha | Anonymous | Dina | Intact Cervix (Kate)

IUDs

IUD insertions are another procedure that involves the cervix that is normalized, but yet fosters a lot of underground testimony about unheard pain. IUD stands for intrauterine device, a small device which is placed through the cervix into the uterus and functions as a long acting reversible contraceptive. Many patients report that they are not given pain medication or numbing medication before the insertion or removal of the IUD, and reports vary widely on how much pelvic pain is involved. The IUD is known for expulsion, where the body’s own mechanisms are able to remove what it sees as a foreign object in the uterus. Additionally, the cervix is often considered to be an emotional and creative center, and the use of an IUD has alarming rates of depression, including a study in Denmark that reported a 40% increased risk of depression for all women and a 220% increased risk for teens (15-19 years old). Could it be related? We don’t know, but one thing is for sure, there is a stark contrast between the testimonials of people who’ve had IUDs vs what most doctors will tell you about the pain and pelvic inflammation associated with the device.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy, or the surgical removal of the uterus, is generally considered a positive procedure in regards to the quality of life of the patient. However there are still questions about how it affects sexual function, and especially in regards to how it may sever the connection between the uterus and the brain. Sometimes the cervix is removed during hysterectomy, but it doesn’t always have to be. Harroth Hasson MD states “the cervix is not a useless organ and should not be removed during hysterectomy without a proper indication… loss of a major portion of the uterovaginal plexus through excision of the cervix is bound to have an adverse effect on sexual arousal and orgasm in women who previously experienced internal orgasm.” Evidence suggests that 3 months after hysterectomy, there was a small but significant reduction in sensitivity to cold and warm stimuli at the anterior and posterior vaginal wall, whereas clitoral sensitivity was not affected. There are higher rates of loss of orgasm when the cervix is removed compared with when the cervix is spared in a hysterectomy procedure. There are also psychosexual effects reported such as a “loss of interest in sex, difficulty becoming sexually excited, and vaginal dryness.” Hormone therapy did not reduce these long term effects either. This area is also generally poorly studied, as few studies have even considered asking about the role of the cervix in their sexual response after hysterectomy. “Thus the absence of evidence of a sensory role for the cervix in sexual response should not be construed as evidence of its absence.” [3]

Respecting the Cervix Is More Than An Individual Responsibility

We are often bombarded with cervical cancer screening campaigns like the “#loveyourcervix” campaign but I’m learning that these campaigns shift the focus onto the individual to be “responsible for their health by attending a screening”. This leaves the topic of medical harm that is done to the cervix conveniently out of view. There needs to be a serious indictment of these cervical procedures, which are based in the fallacy the the cervix does not have much of a function, and can’t feel pain. These ideas are not only outdated, they are responsible for generations of violence and female castration. This should alarm us. We will continue to push back and declare: The Cervix Has Nerves!